Japanese Garden Tools Vs. American: What’s the Difference?

You may have seen Japanese gardening tools popping up more in stores and online. Sure, they’re… Read More

I recently had the pleasure of interviewing world-renowned metal shaper Fay Butler, who lives and works in Hardwick, a small town in Central Massachusetts. Oddly enough, I met him in an ice cream booth at the Hardwick Community Fair, America’s oldest fair. Fay is the President of the festival and I was working as a volunteer, scooping ice cream. I knew him by reputation, not personally, but the moment we started talking I knew this was a guy who I wanted to learn more about. I studied industrial design at the Rhode Island School of Design, in Providence, so I had more than a casual interest in meeting with the legendary Fay Butler.

Fay Butler, in his metal shop. Behind him is the iconic Bridgeport milling machine, with an array of drill bits and chucks at the far right.

I was excited to talk metal and see some machines in action at Fay’s workshop. But I was pleasantly surprised to find an engaging philosopher who thought long, hard and constantly about the world around him and his place in that world. It was quickly clear that Fay has spent a lot of time in deep thought and soul searching. At a young age, he worked at his father’s garage in Hardwick, an early introduction to automobiles and mechanical things that would come in handy later. He openly discussed his early traumatic experiences, including his parents’ ugly divorce, and how dealing with this upheaval shaped him. He has shown an amazing capacity to transform those early hardships into strength.

Fay Butler Fab/Metal Shaping is in the back of a non-descript country garage in Hardwick, Mass. The business is a four-in-one, with working woodshop, machine shop, metal shop, and upholstery shop on the premises. Fay is an expert in all four of these disciplines, and many other things.

Fay largely raised himself as a teenager, and learned about his capacity for endurance through running. He wasn’t a naturally gifted runner, but he came to believe that he could push himself harder than most people. He realized he could suffer and then turn that suffering into fortitude. Here was one of the best metal benders in the country, riffing on things like the importance of facing your internal demons to reach your potential, and the power of intimacy with the things you create. I came away impressed that hardships that would have stopped most people seemed to propel him.

After high school, Fay put himself through college, first earning a business degree. He continued his education by deciding to study industrial art and design at Fitchburg State University, in nearby Fitchburg, Mass. He recalls driving an hour to class, another hour to a job, and then an hour home on a daily basis, while living off very little money; one more example of an extremely driven person. Fay had the forethought and determination to seek out the smartest and hardest teacher he could find, and study under him. All these years later Fay recalled the name of his woodworking instructor, Walter Harris, a man not prone to lightly dole out praise to his students. But Fay won him over with hard work and great persistence.

One of his jobs during college was working for an antique car dealer, a job that would unknowingly set him up for his future calling as a metal shaper. During a trip to a car swap with the antique car dealers, Fay met Larry Amesley, an expert car restorer and owner of Amesley Antique Body Co. in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. They kept in touch, and after graduating from Fitchburg, Fay started apprenticing with Amesley. Fay ended up spending years at Amesley Antique Body, honing his craft of metal bending, while expanding his knowledge of both car restoration and the science of metallurgy. “Being a craftsman goes beyond what you produce,” Fay says of those years. “What you produce with your hands needs to become a way of living – and to produce great things you need to learn to love.”

Detail from recent project, restoration of an antique automobile.

Another Fay Butler original: a desk lamp on wheels, a nod to the sensuous curves on classic Detroit automobiles.

Fay worked with Larry for as long as he kept learning new things. He eventually made his way back to Hardwick, where he set up his own business, Fay Butler Fab/Metal Shaping. Along the way, Fay had also learned the art of upholstery (integral to restoring antique cars), and his business includes upholstery, a wood shop, and machine shop, in addition to his legendary metal shop. A master of all trades, indeed. On that contemporary, pop-philosophic notion that it takes “10,000 hours to expertise,” Fay likes to put his own stamp on that trope: “The idea that it takes 10,000 hours of practice to master something is crap – it takes that long to just clear your mind and to start thinking critically.”

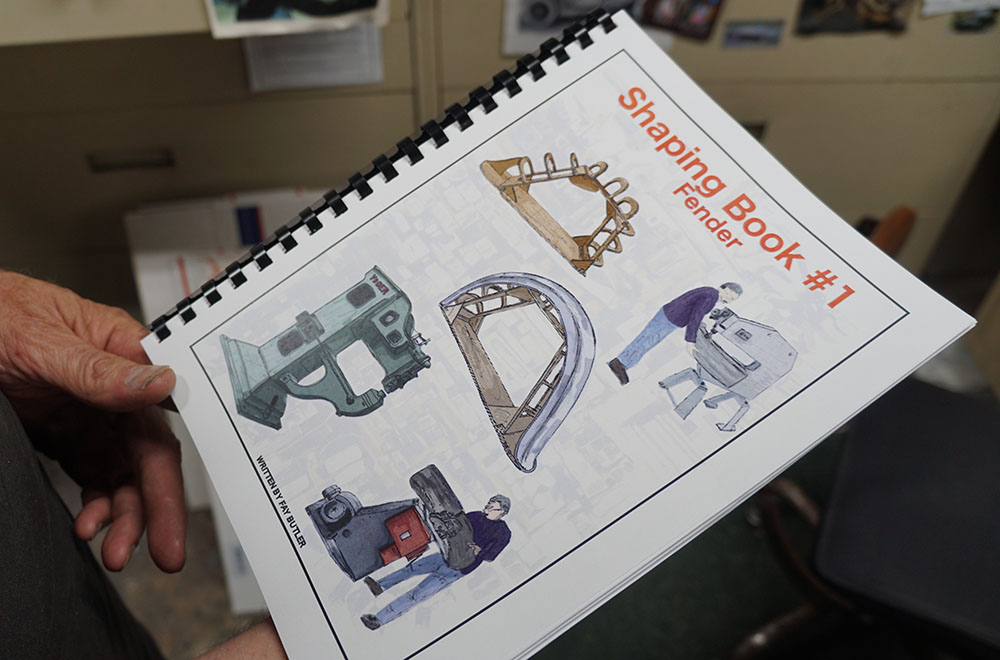

Our conversation moved to Fay’s teaching. Clearly, it’s important for him to impart his hard-earned wisdom on the next generation of metal benders. Fay has given seminars to General Motor engineers, Ford and Chrysler, and he has even worked with Delta Airlines on the restoration of an old DC-3. He runs seminars in “The Principles of Metal Shaping” for the general public many times per year. (You can see an outline of the seminars here.) His most famous pupil was Jesse James, the reality show host and builder of custom motorcycles. The classes are clearly a place where you’ll walk away with a graduate-school level knowledge of metallurgy, in addition to asking soul-searching questions like, “what is blocking my own excellence?” Fay has written several books on metal-shaping and machining, so that the curious can explore the art and science of metallurgy on their own.

One of Fay’s many self-published books about shaping metal.

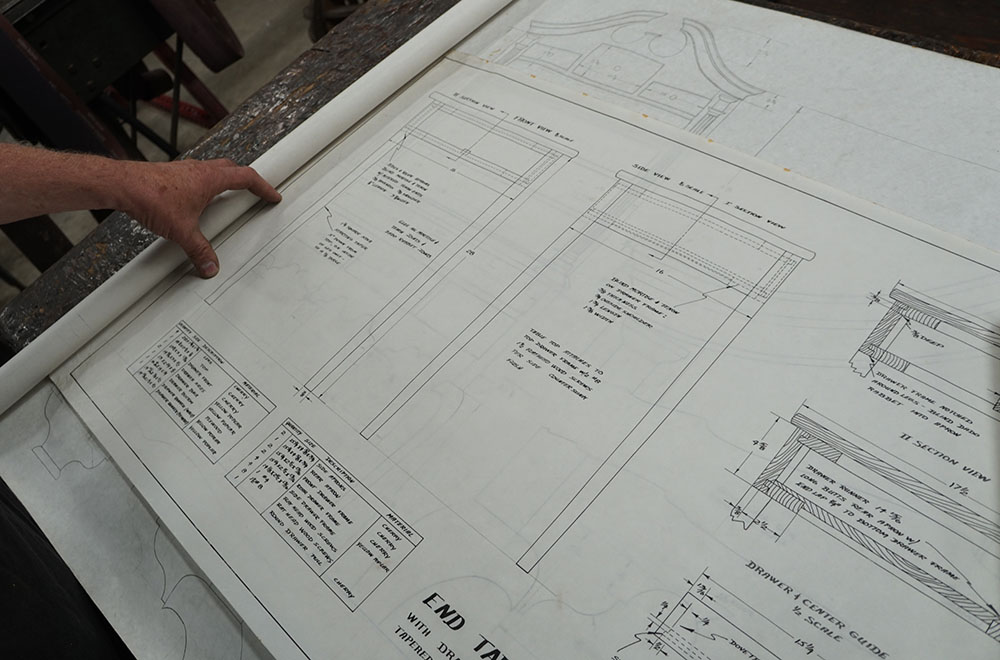

Plans for an “End Table with Drawer and Tapered Legs,” a project from 1988. In addition to his metal shaping renown and prowess, Fay is also an accomplished, professional woodworker.

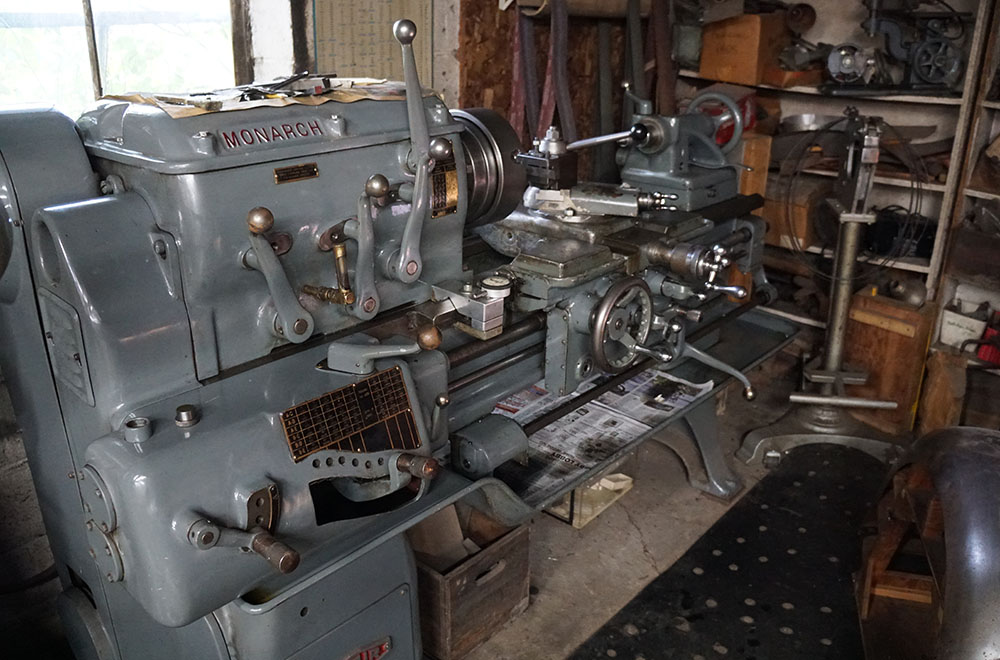

We also discussed tools. As a co-owner of Garrett Wade, a company whose motto is “Where Good Tools Come First,” I was interested in what Fay had to say about his own tools and machines—things that are so integral to his livelihood and his very essence. Fay summed up his tool philosophy like this: “Buy the best tool you can afford – even if that means one that may be worn down but can be rebuilt.” He went on to explain how much you can learn about a tool, by rebuilding it. “It’s not always cost effective to take apart and rebuild tools, but the process is profound in what it does to your mind.” In doing so, Fay felt you built an intimate relationship with the tools of your trade.

A few days after our meeting, I reflected on our wide-ranging conversation. I always find it inspiring to talk with people who chart their own course towards mastery. What sticks with me the most is how determined he was to pursue his own path towards expertise, in multiple disciplines no less. For most of us, so many things crop up in our lives—old demons, new hardships, working to provide for family—that pull us away from our passion. For Fay, there were dozens of reasons he could have gotten sidetracked, but he remained laser-focused on what he wanted and who he was.

A classic Do ALL vertical band saw.

Detail of the Bridgeport milling machine, still running strong after all these years. This is a front view of the machine behind Fay in the portrait, at top.

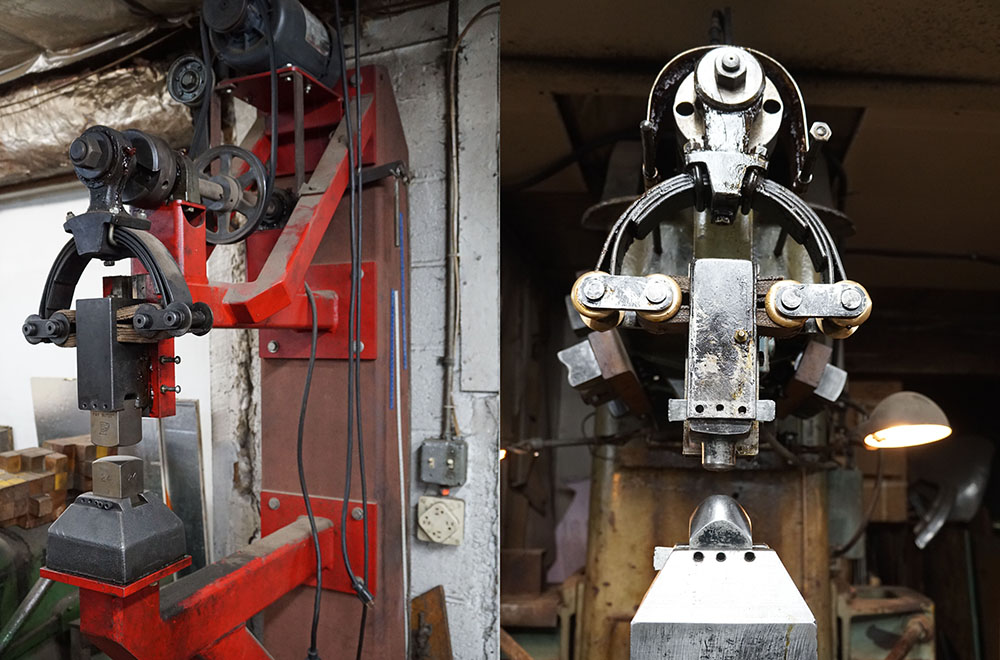

Variation on a theme: two of many metal-forming machines in Fay’s shop.

An array of metal stamps, for use in the metal forming machines.

A Monarch metal lathe. The four levers near the ‘Monarch’ logo control the speed of the lathe.